Scarring is a type of marked imperfection on the skin that comes in various forms and properties. All skin types are vulnerable to scarring, and scarring can inflict on almost all parts of the body. The most common types of scars are atrophic, hypertrophic, and keloid scars.

Scarring can occur as a trauma either from an accident or even from an elective operation. As a result of these scars, the person may experience discomfort that hinders their joint movements, constant irritation and itchiness, and psychological distress. Abnormal and prominent scarring can invite physical, psychological, aesthetic, and social discomfort.

Types of Scarring

Atrophic scarring

Most patients who seek a dermatologist’s help in respect to scarring come into the office with the intention to ameliorate visible atrophic scars found on the face or any revealing part of the body. This type of scarring can be present in almost all parts of the body in the form of sunken, pitted, and chicken pox-like residue or other irregular depressions on the skin. Its edges can appear jagged. Factors that can lead to this type of scarring are muscle or fat volume loss, the degeneration of collagen production, and/or any other damage prevalent under the skin.

These scars can become permanent if they remain untreated. Therefore, it is prudent on the part of patients to seek out and proceed with immediate treatments, such as treatment involving fractional lasers or selective waveband technology (SWT). Other treatments that can alleviate this scarring include hyaluronic acid fillers such as Stylage, subcision, microneedling, chemical peels, or medical micropigmentation. Atrophic scars can come about through accidents or surgical trauma and include severe acne scars and chicken pox.

Hypertrophic scarring

In comparison to atrophic scars, hypertrophic scars are usually darker and more pigmented. They are also raised compared to the surrounding skin but stay within the wound boundaries. They are usually a result of thermal damage and/or trauma on the reticular dermis. Usually, hypertrophic scars will impede movements.

This type of scar can continue to thicken for up to six months. This thickening can often restrict movements, and it may take up to two years for this scarring to heal fully on its own. However, if these scars show no improvement after a year, there is a chance that they can develop into a keloid scar.

Treatments that can help remove hypertrophic scars are micropigmentation, scar revision surgery, steroid injections, silicone sheeting gel, and electrosurgical excision. It is also recommended for the patient to follow through a session of steroid injections and undergo one or two SWT/laser sessions and use hydroquinone cream for color correction.

Keloid scarring

Keloid scars have proven to be most clinically challenging in terms of renewal. The scarring often appears as a benign, fibroproliferative tumor growth that comes about as a result of excess collagen activity at the site of skin trauma. The scars have a rubbery and mildly tender texture, are well-demarcated, and marked by telangiectasias. In some cases, ulcerations may occur. The lesion color can appear pink or purple due to hyperpigmentation. Unlike hypertrophic scars, keloids tend to extend their territory beyond the original wound.

Unlike atrophic and hypertrophic scars, keloids are often the result of a deep dermal injury. Some of the causes may include piercings, vaccinations, surgical procedures, lacerations, and burns. While normal wounds would heal with a balance between the degradation and deposition of cellular activity in the extracellular matrix, keloids oversee over-aggressive cell activity. However, the potential for keloid scar development is often multifactorial and hereditary and is more prevalent in darker skin patients. Keloids are more abundant in early adulthood and the 20s to 30s and gradually decrease.

The neocollagenesis growth typically begins as soon as three months after the injury. However, the visible development of keloids tends to take place several years after the initial insult. The growth persists without any signs of regression and no potential for malignancy. It usually develops at the shoulders, ear lobes, cheeks, anterior chest, and skin that overlies joints. For patients, these scars can feel uncomfortable, and patients may feel pain, itching, and hyperesthesia due to the contractions of the excessive formation.

Keloids histologically consist of a thick and disorganized bundle of collagen fibers. These bundles are usually hypocellular type I and III, pale-staining, and have a low presence of nodules. Blood vessels are also present in these growths, and they are often scattered and dilated. The detection of excessive fibronectin has also proved its influence on the formation of keloids. Compared to other scars, keloids also have an extended inflammatory period, as pro-inflammatory cytokines and cells stimulate fibroblastic activity.

The treatment modalities for keloids are electrosurgery, steroid injections, and intralesional cryosurgery.

Types of treatments

The types of treatments that are available to treat scarring include:

- Fractional laser resurfacing;

- Medical micropigmentation;

- Selective waveband technology (SWT);

- Electrosurgery and steroid injections.

Fractional Laser Resurfacing

This treatment is a popular choice for the treatment of atrophic scarring, striae gravidarum (scars formed during the last trimester), and surgical scarring.

Fractioned non-ablative lasers can project a large number of small columns per square centimeter. The spots of energy elicit a thermal reaction to the dermis that encourages natural injury and repair. This often leads to a reversible necrosis state that promotes neocollagenesis, angiogenesis, and the structural rearrangement of the scar tissue and the dermis.

This treatment is recommended to be carried out in at least three sessions in six-week intervals. For this treatment, use a topical anesthetic, such as LMX 4 or Emla, before proceeding with the treatment so as to reduce any pain in the patient. The advantage of this treatment is the lack of downtime required. Patients may feel a slight sunburnt feeling and observe mild erythema; however, these developments occurring greatly depends on the patient’s sensitivity.

Medical micropigmentation

Medical micropigmentation is a procedure that replenishes the pigmentation of a scar to reduce its jarring visibility against healthy skin. This procedure deposits appropriate colored pigments into the dermal layer as a means to restore the dermal structure or reestablish the color in an achromia. In other words, the treatment attempts to camouflage the treated scar.

To achieve a similar color match, examine the scar and the neighboring skin closely. Certain skin tones may require blending selected pigments together. It is not advisable to perform re-pigmentation when the scar is pink-red or pink in color, both of which indicate the scar has yet to heal thoroughly. If the patient’s scar is still within this stage, it is recommended that they take other additional treatments such as laser or SWT treatment to reduce the redness of the scar prior to medical micropigmentation.

This treatment may require up to four sessions in order to rebuild the damaged tissue, depending on the severity and size of the area. During consultation, patients will be advised on the expected number of treatments and told to undergo maintenance sessions every 12 to 18 months. It is important to pursue treatment, as the scars may gradually reappear with time.

The types of scars that can be addressed using micropigmentation are the following scars:

- Scars or cuts from broken glass;

- Plastic surgery scars, especially post-facelift scars;

- Burn scars;

- Hypertrophic scars.

Patients need not worry if the treated area appears red or if they encounter capillary breakage similar to the original scarring during and after the procedure. Certain areas with intense hyper-pigmentation may not be appropriate for this treatment, since the needle puncture may exacerbate the condition. To correct these areas, a 4% hydroquinone cream can help to reduce the color. Similarly, the scar’s thickness also plays a role in the final pigmentation retention and outcome. Certain scars may respond inefficiently to this treatment; this necessitates additional sessions. In other cases, the pigment will be retained but will inadvertently create uneven dark spots. This can be remedied using a 0.1% tretinoin cream and chemical exfoliator.

Like most treatments, diligent aftercare is crucial for protecting the patients from any potential infection. Part of the healing process includes the appearance of inflammation, redness, and scabbing, all of which can subside within four to seven days. It may take two weeks after the initial treatment for the scar to appear fully camouflaged.

Electrosurgery and steroid injections

It has been determined that the combination of both electrosurgery and corticosteroid injections is effective for 50100% keloids. In the first stage, an electrosurgical device destroys and burns selected tissue by passing a low-power high frequency current. A probe is directed to the target area and delivers the electrical pulses. Since different areas of the skin have different thicknesses and sensitivities, the output power voltage needs to be adjusted accordingly. A well-equipped device offers a variety of tip sizes, electrodes, and forceps that are applicable for different types of scarring and skin. For patients who have multiple scars and/or large scars may require a topical or local anesthesia, as it may improve their comfort during this procedure. For small skin lesions in thick skin, anesthesia may not be necessary.

Steroid injections without issue can be used after this treatment to manage the appearance of scarring and/or pain. However, as these injections are known to leave an abrasive wound, patients are recommended to precisely follow the designated aftercare methods, ensuring to ward off any potential infection. Such aftercare methods include the following: Cleaning the treated area with saline wash, applying antibiotic ointment, and applying and wearing the dressing correctly. The physicians designated for such a treatment have to be fully trained and comfortable with the necessary equipment to avoid any injury, burns or other careless mistakes.

Corticosteroid injections are competent at suppressing the inflammation that comes about with the removal of keloids. It also obstructs the cell proliferation and increases the vasoconstriction properties in the scar. It is advised that these injections are given every two to six weeks for gradual improvements to appear. The side effect that can occur from this injection, however, is the presence of network telangiectasia as a result of constant needle assault, trauma, or thinning to the scar tissue. Telangiectasia will gradually resolve as the scar tissue develops a thicker dermal layer. If the telangiectasia is persistent, use a laser/SWT session to remove the affected area.

The treated area may also exhibit pigment changes. Usually, it will return to normal once the injection sessions have come to an end. If hyperpigmentation or post-inflammation hyperpigmentation persists, a 4% hydroquinone cream or topical product can be used to lighten the scar and treat any post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Selective Waveband Technology (SWT)

Redness, also known as erythema, may appear not just after post-acne inflammation but also from medical situations such as scarring after a surgery and scarring that occurs during the preparatory procedures of medical micropigmentation. A laser treatment can help to reduce the redness associated with a flat scar, especially the light salmon-colored scars, which can be rectified using a sub-millisecond pulse.

Follow up a surgery with SWT leaser treatment in the following three weeks and after removing or dissolving the sutures. Practitioners must be fully trained and well-versed with the required energy levels and pulse duration for the affected area.

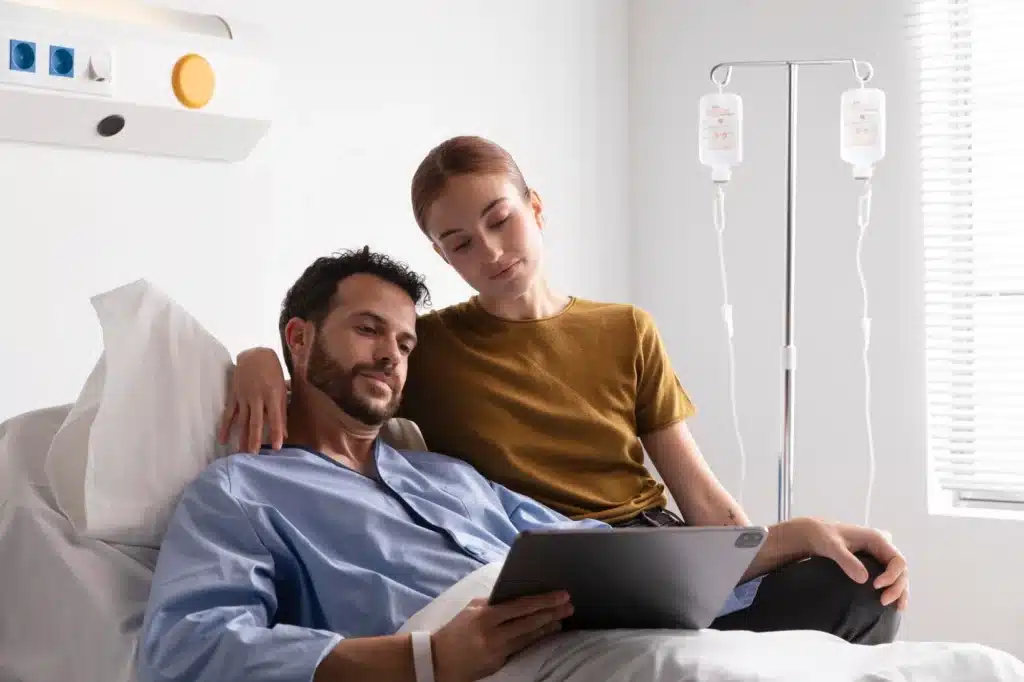

Surgery

For severe scars, surgery can help to correct the appearance of said scars by changing the form of the affected area and revealing a tight scar that is located near a joint. This method aims to improve the articulation and movement of the scarred body part with less friction and/or irritation.

The process, known as scar revision, involves the removal and excision of the scar tissue. The new wound is closed and healed via the primary intention. For deeper cuts, a multi-layered closure may be optimal for its healing process and to avoid causing the emergence of depressed scars. It is often used for hypertrophic or keloid scars.

Other treatment modalities that are associated with surgical excision are pressotherapy and silicone gel sheeting. By performing surgery on a scar, there is a risk of the surgery causing the development of a new scar that may take up to two years to heal. There is also the risk of the patient developing new keloid and hypertrophic scarring post-surgery. The recurrence rate for a keloid scar after a surgery is between 50 to 80%.

Conclusion

The large range of products available may make choosing an appropriate treatment intimidating for both patients and practitioners. Knowing and understanding the type of scars and the treatments that are in use may help patients be more aware of their options and may make them have realistic expectations. Patient care is crucial for ensuring a satisfactory treatment. This means patients also deserve to be fully informed during the medical consultation and subsequent treatment session.

By knowing the scarring type of the patient, practitioners can offer an adequate treatment that can provide optimal results with minimal pain and adversity.

References:

[1] Sund B., ‘New developments in wound care’, PJB Publications, (2000), pp.1-255.

[2] UK Health Centre, ‘Atrophic Scars’, (2016) http://www.healthcentre.org.uk/cosmetic-treatments/scars-atrophic.html

[3] Gauglitz GG, Korting HC, Pavicic T, et al., ‘Hypertrophic scarring and keloids: pathomechanisms and current and emerging treatment strategies’, Mol Med., 17 (2011), pp.113-125.

[4] Har-Shai Y, Mettanes I, Zilberstein Y, et al., ‘Keloid Histopathology after intralesional cryosurgery treatment’, J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 25(2011), pp.1027-1036.

[5] Thomas DW, Hopkinson I, Harding KG, Shepherd JP, Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg., 23 (1994), pp.232-6.

[6] Beasley K, Dai JM, Brown P, et al. Ablative fractional versus nonablative fractional lasers-where are we and how do we compare differing products? Current Dermatology Reports. 2013;2:135143.

[7] Harithy Ra, Pon K. Scar treatment with lasers: a review and update. Current Dermatology Reports. 2012;1:6975.

[8] Bogle MA, Yadav G, Arndt KA, Dover JS. Wrinkles and acne scars: ablative and nonablative facial resurfacing. In: Raulin C, Karsai S, editors. Laser and IPL Technology in Dermatology and Aesthetic Medicine. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer; 2011. pp. 289297.

[9] Consulting Room, “Medical Micropigmentation.” https://www.consultingroom.com/Treatment/Medical-Micropigmentation

[10] Johnson, S., ‘Treating Scars’ Aesthetics Journal. 2016. https://aestheticsjournal.com/feature/treating-scars-1

[11] Selective Waveband Technology (Denmark: Ellipse, 2016) http://www.ellipse.com/en/Clinical/ Selective-Waveband-Technology

[12] Leventhal D, Furr M, Reiter D, ‘Treatment of keloids and hypertrophic scars: a meta-analysis and review of the literature’, Arch Facial Plast Surg. 8(6) (2006), pp.362-8.